Gartering Applause:

Vestrimania in London, 1780-81

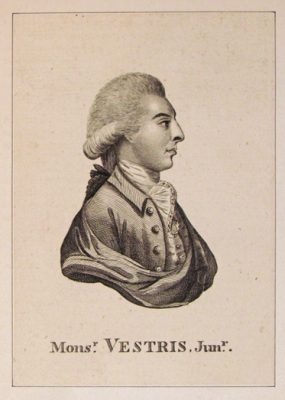

Vestris garters, anyone? What about a length of Vestris blue ribbon? Hey, is that a “Vestris grin” you’re giving me?!1 In the early winter of 1780, “Vestris” became the buzz word of fashionable London. It was a name synonymous with supreme excellence, French caprice and the latest mode. The man who inspired “Vestrimania” was the twenty-year old dancer, Auguste Vestris, then making his first visit to London accompanied by his celebrated father, Gaetan. Feted by the beau monde and befriended by the Duchess of Devonshire, Auguste dazzled audiences at the King’s Theatre with his extraordinary virtuosity. Gaetan did his bit for Vestrimania, too, fielding requests for dancing lessons from all the leading families of the day.

Marie-Jean Augustin (Auguste) Vestris was among the brightest stars of eighteenth-century ballet. His contribution to dance was also far-reaching, thanks to his impact on ballet in Britain and the changes he modeled for later generations of dancers. His debut at the Paris Opera in 1772 marked the beginning of a career that spanned four decades. Meticulously trained by his father, Auguste inherited the physical gifts of both his parents, especially those of his mother, the popular dancer Marie Allard. A lively and petite individual, well-suited to comic and character roles, Allard was noted for her technical facility and expression. Auguste, lacking both his father’s stature (Gaetan was nearly six-feet tall) and his patrician features, therefore followed his mother by excelling as a demi-caractere dancer. Yet, although Auguste’s “astounding elasticity and speed, combined with his expressive countenance and lively spirits” made him excellently suited to this genre, Auguste rapidly emerged as a dancer of unusual versatility.2

At the beginning of Auguste’s career, the division of dancers into three main genres—noble, demi-caractere and caractere—remained an important aspect of eighteenth-century ballet. The genres were used to categorise dancers according to their physique and way of moving, affecting the vocabulary they learned and the characters they portrayed. By the mid 1770s, the growing popularity of ballets d’action (narrative ballets) was beginning to diminish the relevance of this convention. But it was Auguste who finally rendered the three genres obsolete through his natural ability and desire to explore the full range of his talent. For instance, at his London debut in 1780, he appeared in both serious (noble) and comic (caractere) roles, leaving the public “most agreeably surprised to see his superlative excellence in each distinct ballet.”3 By 1807, Jean-Georges Noverre ruefully conceded that Auguste had “eliminated the three well-known and distinct genres,” creating “a new style which was successful because everything succeeds with this dancer.”4

Audiences everywhere were enraptured by Auguste’s technical accomplishment and the nuanced characterization and charm he consistently delivered. The Mercure de France pronounced that his “prodigious talents have to be seen to be believed,” and remarked on his precision, strength, his graceful build and intelligence.5 Lord Pembroke, a long-time observer of opera and ballet in England, enthused “young Vestris is a wonderful fellow. All I have hitherto seen are quite nobody to him.”6 In 1790 when Auguste performed in Lyon, a Russian visitor noted that the theatre “hummed all around us like a beehive” in expectation of Auguste’s first entry.7 “What a figure! What agility! What balance!” the young Russian gasped after seeing him; “Never did I imagine that a dancer could afford me so much pleasure!” When the audience persuaded Auguste to give an extra performance the following evening, the response was ecstatic. “I think the flighty French could, at that moment, have proclaimed Vestris their dictator,” the Russian wrote, recalling how the applause drowned out the music.

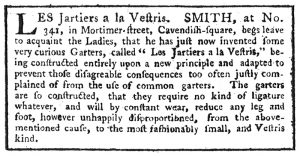

What then of Auguste’s influence on ballet in Britain? Well, it was thanks to Auguste that ballet received the ultimate PR makeover in England in the early 1780s. Long regarded as a minor appendage to the Italian opera, ballet was transformed through Vestrimania into a legitimate part of British theatrical culture.8 It became, for the first time, the subject of separate reviews and notices, and a hot topic of public discussion.9 Auguste’s popularity among women, in particular, created a new market for ballet-related goods and services, and his success paved the way for a string of acclaimed dancers to visit London during subsequent seasons. The Vestris garters, described in the advertisement here, are the most curious ware that Auguste inspired. Used to keep stockings up, eighteenth-century garters were normally tied just below the knee and were fashioned from a variety of materials including satin and leather. We can judge from Mr Smith’s address in London’s West End that the Vestris garters were designed for upper-class ladies. But were they are a luxury for the gullible? Or a genuine physique-changing innovation? That is a matter best left to your imagination!

- Morning Herald, 25 May, 12 April and 12 May 1781. ↩

- August Bournonville, My Theatre Life, trans. Patricia N. McAndrew (London: A. and C. Black, 1979) 458. ↩

- Morning Post, 18 December 1780. ↩

- Noverre quoted in John V. Chapman, ‘Auguste Vestris and the Expansion of Technique,’ Dance Research Journal 19, no. 1 (1987): 11-18. ↩

- Mercure de France, October 1772, quoted in Ivor Guest, The Ballet of the Enlightenment (London: Dance Books, 1996) p. 55. ↩

- Lord Pembroke to Sir William Hamilton, 6 February 1781. Lord Herbert, ed. The Pembroke Papers (1780-1794): Letters and Diaries of the First Earl of Pembroke and His Circle, 2 vols (London: Jonathan Cape, 1942-50) p. 87. ↩

- N. M. Karamzin, Letters of a Russian Traveler 1789-1790: An account of a young Russian gentleman’s tour through Germany, Switzerland, France and England, trans. and abridged by Florence Jonas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1957) pp.171-3. ↩

- Caitlyn Lehmann, ‘Fashionable Society, Ballet and the King’s Theatre, 1770-1800,’ PhD diss. (University of Melbourne, 2012) p. 99. ↩

- Judith Milhous, ‘Vestris-Mania and the Construction of Celebrity: Auguste Vestris in London, 1780-81,’ Harvard Library Bulletin, n.s., 5, no. 4 (1994-95): 30-64. ↩

Leave a Reply