Madame Rose Parisot, ‘Attitudinarian’

Hello everyone! I thought it was high time to revisit this piece on Madame Parisot which originally appeared in Dance Australia. After it was published, I became a little concerned one or two factual errors had crept in. So I’ve gone a-rummaging around in my notes, and here ’tis now with references (at least those I could relocate). Do hope you enjoy reading about Our Lady of Euclidean Angles. It’s reminded me Parisot really deserves to be the focus of a much bigger study…

Pick up any dance magazine today and you’ll see dozens of photos of bright young women holding their legs high in arabesques, attitudes and dazzling six o’clock penches. And you may think no more of it. But have you ever paused to consider the very altitude of those legs? Once concealed beneath heavily adorned dresses, dancers’ legs have enjoyed a decidedly upwards progress since the end of the eighteenth century. It’s a trend that has persisted despite recurrent bouts of social conservatism in the West. High altitude legs are now a regular part of our modern ballet aesthetic, defining men and women alike by a physical image that is sculptural, aerial and acrobatic.

No one can say when the first dancer fixed a six o’clock penche. However, Madam Parisot is undoubtedly a contributor to the history of exalted shanks. Trained by the Paris Opera’s ballet master, Jean-Antoine Favre Guiardele.1 Parisot actually spent much of her life in England. Following an early engagement in Rouen as a premiere danseuse, she moved to London in 1796 where she made her first appearance in a short divertissement at the city’s prestigious King’s Theatre.2 Aged about eighteen at the time, Parisot may have had good reason to leave France behind. According to contemporary reports, her father was the noted French dramatist, Pierre Germain Parisau, who had been guillotined in 1794.3 Parisot’s success in London was immediate with critics acclaiming her beautiful figure, grace, and “positively magical” balance.4 However, it was her “attitudes” that held audiences spellbound: “for her person was almost horizontal while turning as on a pivot on her toe.”5

Contemporary accounts offer differing impressions as to how these attitudes were performed. One observer wittily dubbed them her “pedal sostenuto”, and wrote “It is really surprizing to see her keep upon one leg so long, and even change her position in that state. She does not, however, sacrifice grace, for in her allegro dancing she is elegant as well as lively.”6 Making her “fantastic positions”7 all the more impressive was the height at which Parisot held her working leg, which earned her the attention of satirical artists. Shown above, A Peep at the Parisot was one of two humorous prints that rewrote iconographic convention by pointedly depicting the dancer with her leg raised 90 degrees to the floor.8 Together with Richard Newton’s illustration, simply titled Madamoiselle Parisot, the two prints brought to a close the pictorial tradition of depicting female dancers lightly springing from the ground with billowing skirts. After 1796, it was the contrived height to which dancers raised their legs that increasingly dominated ballet’s representation in popular culture.

Nowadays, viewers often assume that A Peep at the Parisot intends to ridicule Parisot’s dancing. But, like a number of ballet-themed prints produced during the 1790s, the real targets of Isaac Cruikshank’s satire are the public figures looking on. Among the men seen in the audience are, from right to left, political foes Charles Fox and William Pitt (who looks over Fox’s shoulder); the playwright and politician, Richard Brinsley Sheridan; and the lecherous Duke of Queensberry whom everyone loved to hate. Cruikshank here invites us to ask: are the men connoisseurs of Parisot’s art? Are they respectable, or are they merely after a glimpse of her privy parts? Such questions were very topical in the 1790s as a resurgent evangelical movement sought to influence public morals and the nation’s leadership. Matters came to a head in 1798, when the Bishop of Durham denounced ballet dancers for their corrupting influence on British youth. For several months, Parisot and her colleagues found themselves pawns in an intense and highly emotional debate over the influence of religion on theatre and personal freedoms.

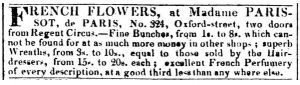

Happily, Parisot weathered the storm and theatre-lovers took her to their hearts. For some ten years she danced regularly both at the opera house and at Drury Lane, appearing in ballets such as Alonso e Cora, Le Bouquet, Little Peggy’s Love, and Sappho and Pharon (provocatively subtitled “A Grand Erotic Ballet”). Her retirement in 1807 was precipitated by marriage to a successful local florist, Mr Hughes, by which time she had carefully saved an impressive £12,000 from her performances.9 Given her husband’s occupation, might it be ‘our’ Parisot whom we catch sight of again in 1827, when the Morning Chronicle published an advertisement for French flowers and perfume, available from “Madame PARISSOT de PARIS” at No. 324 Oxford Street?10 Our last confident glimpse of her is in Paris in 1837, where it was reported she had been living “for many years”.11

Parisot’s attitudes clearly mark an important step in the development of modern expectations for dancers’ flexibility and poise. Besides modelling higher elevation for the legs, Parisot adopted, too, the looser, more revealing neoclassical garb of her time, which enhanced, for all dancers, the visible physicality of their art. Curiously, despite her considerable popularity, Parisot’s first name is still the subject of some confusion, being given by historians as either Celine or Rose. The sources I’ve looked at suggest Rose is most likely. But whether mentioned in newspapers, novels, letters or shown in pictures, Parisot is simply Parisot, the famous dancer and “attitudinarian”.12

- Having found this information about Favre Guiardele while researching Parisot, I’m afraid the source eludes me now. I’ll keep a lookout… ↩

- Winter, Marian Hannah, The Pre-Romantic Ballet (London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons), p.167; Morning Chronicle, February 10, 1796. ↩

- True Briton, March 8, 1796; Morning Chronicle, March 7, 1796. ↩

- Morning Chronicle, February 10, 1796. ↩

- Morning Chronicle, February 10, 1796. ↩

- True Briton, February 15, 1796. ↩

- The Monthly Mirror, February 1796. ↩

- Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library. “A peep at the Parisot with Q in the corner” New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/0eaba0f0-d70e-0132-8961-58d385a7bbd0. Image featured above with permission. ↩

- Gentleman’s Magazine, December 1807, p.1171; The Ipswich Journal, December 26, 1807; The Lancaster Gazette and General Advertiser, February 6, 1808. Figures vary as to how much precisely she had saved, but clearly it was known to be a considerable sum. ↩

- Morning Post, May 25, 1827. ↩

- The Musical World, October 1837, p.126. With thanks to the Wiki contributor who spotted this. Nice one. ↩

- This article first appeared in the Dec 2011/Jan 2012 issue of Dance Australia. It’s republished here with references and minor amendments. ↩

Leave a Reply