Mao’s Last Dancer: The exhibition

15 August 2018

Li Cunxin may be making waves as the adroit, go-getting artistic director of the Queensland Ballet. But to millions he is best known as Mao’s Last Dancer, the man whose best-selling biography spawned a movie, a charming children’s book, and (almost as an afterthought) the current temporary exhibition at Melbourne’s Immigration Museum.

Having been to a few dancer-focused exhibitions in my time, I admit my expectations weren’t overly high. It’s notoriously difficult to turn the vibrant physicality and energy of a dancer’s career into an illuminating exhibition – birth certificates, a few black and white photos, a film clip and the odd sparkling costume will only take the casual visitor so far. And for the crotchety teenage lass who stumped about the gallery on crutches (announcing loudly to her mother after mere minutes that she’d “seen everything”) clearly there weren’t the dynamic visuals to compensate for a short attention span. However, all things considered, the museum has done an excellent job with the materials to hand, in particular, by adding an all-important element of context to Li’s story with a small number of well-chosen objects representing his upbringing during the era of the Cultural Revolution in China.

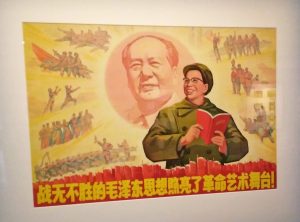

Poster of Jiang Qing (Madame Mao), with the caption: “The invincible thought of Mao Zedong illuminates the stage of revolutionary arts.”

For those used to ballet’s cosy image as a cotton wool entertainment of fairytales and romantic tragedies, all at safe a-political remove from reality, the display carries firm reminders that ballet always carries a political charge – it’s only a question of how high the voltage and what kind of current. One of the most intriguing objects was a 1969 poster depicting Madame Mao and her husband surrounded by scenes from “the stage of revolutionary art”. As a work of poster art, it is bold, message-laden and compelling in its blend of visual immediacy and more subtle details for the viewer to interpret. It’s a shame the accompanying placard did not identify the individuals productions shown, deemed to have benefited from Mao’s “invincible thought”. Perhaps that’s a scene from The Red Detachment of Women shown top right? I wonder if Melbournians could conceive scenes from a production by the Australian Ballet being included in some similarly nationalistic propaganda piece?

Eye-catching, too, was this pair of block-print designs for China’s ballet company dating from 1968. Aside from their aesthetic appeal, they also prompt reflection on how much the evocation of character – and strength of character – have fallen out of favour with dance-image makers today. These prints convey a rhapsodic sense of freedom, independence and purpose, all in a work-a-day mode of social collectivity, which, curious to say, we might only find in the imagery of Ashton’s La Fille mal gardee today.

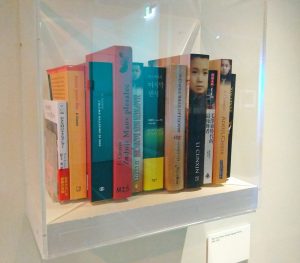

For those familiar with the narrative of Li’s “leap to freedom”, there are political resonances aplenty in the documents and letters associated with efforts to enable Li to remain in America. Those unfamiliar with his backstory may find the cabinet displays of paperwork a little dry, but visitors should at least be able to discern the remarkable link that Li’s story provides between two utterly opposed political orthodoxies. Yes, there are also the sparkling costumes, the wall of black and white photos, and loops of grainy file footage. But as a biographical display and a brief visual encounter with two disparate cultures and their ballet traditions, ‘Mao’s Last Dancer: The exhibition’ is well worth a look.

Featured image on homepage: Posters for The White Haired Girl, 1968.

Where: Immigration Museum, Melbourne, Australia

When: Until October 7, 2018

Cost: Free with general entry fee to the museum.

Leave a Reply