Edouard Espinosa and the world of early British ballet

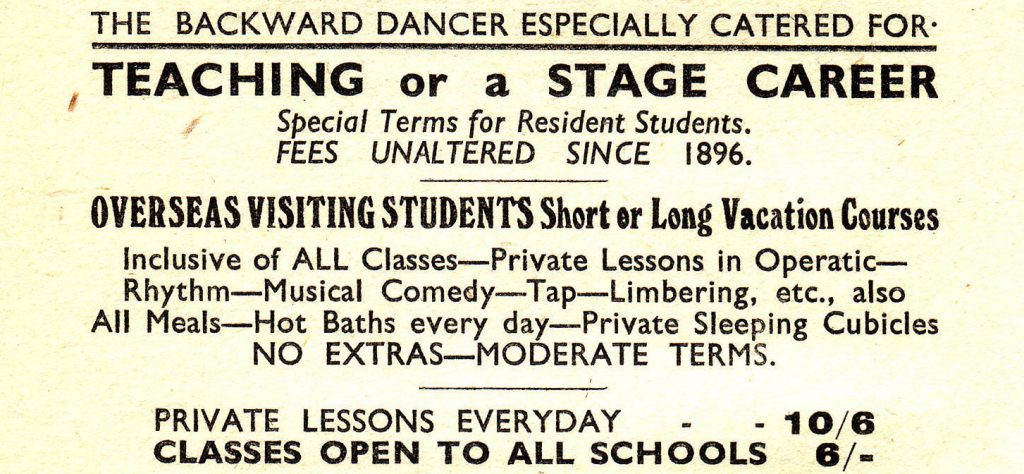

Looking for a ballet school with boarding facilities? In war-exhausted Britain, you wouldn’t pass up one with daily hot baths and private sleeping cubicles! The confidence of this 1945 advertisement for the Espinosa School belies the privations of the time and the puritan standards that still characterized the mainstream English boarding school experience. Today, its pitch to the “backward dancer” might seem quirkily un-PC. But after years of war, it’s easy to imagine young dancers anxious to compensate for irregular training or feeling insecure in the face of returning competition.

Nowadays, the Espinosa establishment in south-west London is the headquarters of the British Ballet Organisation (BBO). Offering syllabuses in classical ballet, jazz, tap and modern dance, the BBO is among the UK’s leading dance examination boards and retains a close alliance with the Espinosa family.

A descendant of Spanish Jews, born in Moscow, raised in Paris and hailed for his work in Britain, Edouard Espinosa (1871-1950) is a colourful figure who links the theatrical worlds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The son of professional dancers, Edouard inherited his parents’ restless characters and their esteem for theatre’s infinite variety. His father, Leon, enjoyed a diverse career as a gifted character dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet master, making an impression wherever he went with his large nose and diminutive stature (Leon was just 4’10” tall!). In an era when ballet regularly featured in music hall entertainments alongside pantomimes and comedies, Leon and his wife, Matilda, proved extraordinarily adaptable, bending their talents to accommodate whatever opportunities arose. The couple was in Russia appearing in Petipa’s Don Quixote and Trilby when Edouard was conceived. By 1874 they had moved to London, where Leon ran a dance school between commitments at several venues.1 Four years later the family was in Paris organizing dances for the Porte St. Martin Theatre and Folies-Bergere. For Edouard, two unhappy years at boarding school followed while his parents travelled on to Bordeaux, Brussels and Berlin. Only a serious injury to Leon persuaded the family to take a short breather from their peripatetic lifestyle, thrusting Edouard and his brothers into the role of breadwinners.2

However, life in the theatre was not what Leon intended for his boys. Twelve-year-old Edouard initially odd-jobbed with firms selling embroidery supplies, toys and Bohemian crystal, before becoming a sales representative for dental wares. Being briefly apprenticed to a local dentist, he even managed to botch his one and only tooth extraction (on a hapless milkman) before belatedly beginning his ballet training at the age of eighteen. Although well-versed in ballroom dancing, Edouard was not, by his own admission, a great ballet dancer. “He has terrible feet, but wonderful knees and ballon,” remarked his father. The manager of the Royal Aquarium spoke more bluntly after Edouard’s first performance: “if you were not the son of Espinosa you would finish tonight!”3 Determination and practice nevertheless paid off, securing Edouard’s success as a soloist and variety dancer. His natural theatrical flair and mimetic ability earned him steady work in the music halls and, like Leon, he was adept at choreographing numbers for all manner of theatrical presentations. But it was teaching for which Edouard was increasingly in demand as other teachers and talented students gravitated to his methods.

In 1909, the arrival of the Ballets Russes in London galvanized debate about the technical standards and training of British dancers and the future of English ballet. Edouard saw to it that his students attended the Russians’ performances and welcomed the Russian influence on audiences’ taste. He nonetheless disapproved of British dancers adopting foreign names, and despised the effeminacy of the Russian men.4 Where the Russians promoted ballet as a rarefied art form, Edouard retained his commitment to dance as a part of general theatre. His approach was later echoed by his most famous student, Ninette de Valois, who, as a dancer, choreographer and director, consistently encouraged the theatrical and dramatic sides of ballet.

Keen to banish local myths about British dancers’ inferiority, Edouard committed to elevating the standards of Britain’s dance teachers and to promoting British ballet.5 In 1920 he helped found the Association of Operatic Dancing (now the Royal Academy of Dance) but left following disputes over plans for his British Ballet company. The company that eventuated comprised dancers from across the Commonwealth, and managed performances in London and Manchester before disbanding. He subsequently founded the BBO in 1930 with his wife, Eve Kelland. After Edouard’s death his son, Edward Kelland-Espinosa, took over the BBO’s administration.6 The family’s involvement has continued ever since. Presently, Nicholas Espinosa is chair of the Board of Trustees, and the BBO has teachers registered around the world, with active branches in Australia and New Zealand.

Keen to banish local myths about British dancers’ inferiority, Edouard committed to elevating the standards of Britain’s dance teachers and to promoting British ballet.5 In 1920 he helped found the Association of Operatic Dancing (now the Royal Academy of Dance) but left following disputes over plans for his British Ballet company. The company that eventuated comprised dancers from across the Commonwealth, and managed performances in London and Manchester before disbanding. He subsequently founded the BBO in 1930 with his wife, Eve Kelland. After Edouard’s death his son, Edward Kelland-Espinosa, took over the BBO’s administration.6 The family’s involvement has continued ever since. Presently, Nicholas Espinosa is chair of the Board of Trustees, and the BBO has teachers registered around the world, with active branches in Australia and New Zealand.

Passionate, impulsive and a defendant of the traditions he valued, Edouard esteemed dance as an expression of emotion. “If it is not that,” he declared, “it is merely kicking about without soul, initiative or imagination.”

This article was originally published in Dance Australia, Aug/Sept 2011.

- Katherine Sorley Walker, “The Espinosa: A Dancing Dynasty, 1825-1992,” Dance Chronicle, 30 (2007), 171. ↩

- Rachel Ferguson, And Then He Danced: The Life of Espinosa by Himself (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co, 1946), 4-5. ↩

- Ferguson, And Then He Danced, 20. ↩

- Ferguson, And Then He Danced, xiv-xv. ↩

- The advertisement featured here appears in the 5th edition of Espinosa’s The Elementary Technique of Operatic Dancing (London: Espinosa, 1945), which describes “the rudiments of the art” as “demanded by the British Ballet Organization in its Elementary examination” (p.66). ↩

- ‘History of BBO’, http://www.bbo.org.uk/about-us/history-of-bbo.php ↩

I was taught by a Bridget Espinoza at Elmhurst…any relation?

I’m afraid I don’t know the Espinosa family personally, but I believe their ballet connections have continued intergenerationally and through marriage – and, after all, it is a great, distinctive surname to be able to use! Would someone like to help answer this question?

My mother had a dance school in Manchester in the 1930s and it was always a matter of pride to recount how she once danced with Espinosa.

Bridget Kelly Espinosa was married to Geoffrey Espinosa son of Lea, one of Leon’s 3 daughters. They are the parents of Nicholas Espinosa.

Wow, old school ballet. Thank you for sharing this article.

Did Eddie Kelland Espinoza marry an Australian woman by the name of Edna Moncrieff? Or were they ever engaged? There are some newspaper articles stating they were engaged but I can’t see their marriage.

Geoffrey Espinoza taught at an open to the public ‘night school’ on Fleet Street in the early 70’s, I studied with him. His wife was also teaching probably at the BBO. He was great.

I am most proud to be the Godson of Edouard Espinosa. He died shortly after I was born but I well remember scrabbling about in his wastepaper basket at his Worthing house.

My father, George Atkinson – known as Tommy – wrote all the dance music for him to be used in his lessons. Anyone who would like a copy please let me know. [George can be contacted at g#org##atkinson@hotmail.co.uk (replace #’s with letter e) – Caitlyn]