Four Ballerinas and a Tea Tray

The story of what Marie Taglioni, history’s most famous Sylph, Did Next.

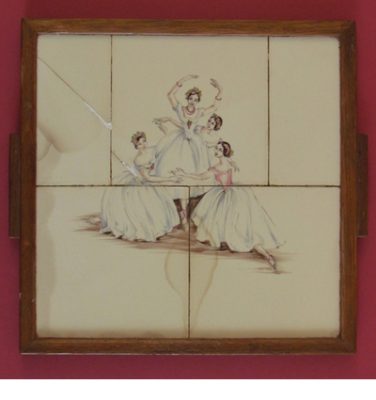

I know what you’re thinking. It’s ghastly, isn’t it? This homemade tea tray had been relegated to an attic before it was thoughtfully palmed off to the first ballet nut who happened by. Honestly, I’m grateful. It was a kind gesture. Really.

Anyway, it might be chipped, stained and entirely superfluous to need. But set aside the amateur execution and the distressing kitschness of it all, and you might find yourself transported to a bustling street in London, just outside Her Majesty’s Theatre, on a balmy summer’s evening.

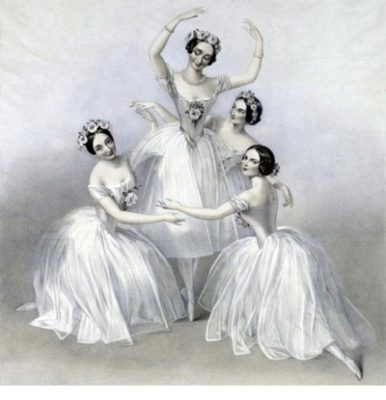

The image on the tea tray is based on A. E. Chalon’s celebrated lithograph of the Pas de Quatre, danced in London in 1845. That’s right. In the original picture, those women were the greatest ballerinas of their age: Fanny Cerrito, Lucile Grahn, Carlotta Grisi and, pride of place in the middle, the sylph herself, Marie Taglioni.

The Pas de Quatre was a late episode in Taglioni’s career, created as the ultimate tribute both to her and to the adulation that Romantic ballerinas inspired. It was no run-of-the-mill dance number, but a carefully managed theatrical event – the brainchild of theatre manager Benjamin Lumley, who saw an opportunity to thrill audiences with a four-nights only, celebrity-fuelled celebration of grace, technique and feminine loveliness.

Luck was on Lumley’s side that summer. Early in the season he announced ambitious plans to bring Taglioni, Cerrito and Grisi together on stage. But when the young Danish dancer Lucile Grahn wowed audiences with her first London appearances in April, Lumley took the canny decision to upgrade the planned pas de trois to a pas de quatre.

The man charged with the delicate task of displaying each ballerina to her best advantage was another doyen of the Romantic stage, choreographer Jules Perrot. With the successes of Giselle, Ondine and La Esmeralda behind him, Perrot was an obvious choice to create an elegant homage to this age of billowing tutus and valiant maidens – and as former dance partner and coach to three of the four ballerinas (only Grahn was a new acquaintance) he knew their talents and their foibles pretty well.

Still, the Pas de Quatre was a trying assignment, and rehearsals had barely begun before a spat in the studio sent Perrot hurrying to Lumley’s office. While all agreed that Taglioni, as the most established star, should dance the last variation, and Grahn as the newest should dance the first, Cerrito and Grisi were disputing who should dance the second and third. Things got personal when Grisi called Cerrito “a little chit!” Lumley pondered the matter and shrewdly declared: “Let the oldest take her unquestionable right to the envied position.” The warring parties smiled, shuffled awkwardly, and agreed to let the choreographer settle matters.

On the night of July 12 the opera house was “crowded to suffocation”, and cheers and stamping greeted the four ballerinas as they entered hand in hand and advanced to the front to curtsey. Each brilliant solo that followed was met with a shower of bouquets, slowly covering the stage with a carpet of fresh petals. By the time the women took up their positions in the ballet’s final sculptural grouping – captured by Chalon – the audience was in raptures.

The Times declared it “the greatest Terpsichorean exhibition that ever was known in Europe”, and the excitement percolated through conversation everywhere. Lumley could not have been more delighted as he recalled how “The varied excellencies of each danseuse were warmly and eagerly canvassed in every club, at every dinner, in every ball-room.” Even Cerrito was forgiven for a last-minute fit of prima-donna pique. Stubbornly refusing to wear a rose garland, she wore, instead, a single rose in her hair, exactly as Chalon depicts her in the picture.

Just three more performances of the Pas de Quatre followed – one attended by that most regal of balletomanes, Queen Victoria – before the ballerinas dispersed across Europe. The event was, if nothing else, an astonishing feat of coordinated scheduling.

In his memoirs, Lumley reckoned the Pas de Quatre “probably formed the culminating point in the History of Ballet in England.” If a determined Irishwoman called Ninette de Valois hadn’t taken English ballet history firmly in hand, Lumley’s observation might still ring true today.

I doubt if Lumley would want my tea tray. And the ladies, I suspect, would deem it in bad taste. And yet I sense it might impress them too. After all, what better test is there of fame than immortalisation on a piece of vintage kitchenalia?

Leave a Reply