Libertine Intrigues:

Cliché-Busting the Opera Girl

“[T]he cliché of a young dancer taken in by a protector of means who is then bled for all he is worth had a real enduring historical truth.” 1

Early on after my great spring forward from medieval studies into the realm of dance and the eighteenth century, I realised that many generalist ballet histories had a quirky hang-up about dancers’ sexuality. It was one thing to know, from my work in medieval studies, that St Jerome had been unnerved by the dancing girls of Cadiz, and that Churchmen sweated profusely at the sight of women performing in public for at least another millenia or so. But why should writers in the modern era lay so much stress on accounts of dancers’ liaisons with wealthy, frequently lascivious, noblemen? Why draw attention to ballet as the rarefied offshoot of some high-class sexual underworld? And why should we do this in the case of ballet when, historically, there is equally a long association between prostitution and women in the acting profession? In fact, right up to the mid-20th century, any woman who performed on the stage was liable to be considered sexually suspect.

The assumption that dancers, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries, were ‘inevitably’ prostitutes or courtesans is, it must be said, deeply entrenched both within and outside the field of dance scholarship. Moreover, there is a seemingly endless supply of evidence to support this claim, in the form of salacious anecdote, titillating iconography and cheerful innuendo. Think of the shadowy gentlemen abonnés in the margins of Degas’ paintings of dancers – we all know what they’re doing backstage at the Paris Opera, don’t we? Or consider the surprise outburst by the Bishop of Durham in 1798, when he stood up in the House of Lords to denounce French dancers for their pernicious influence on British youth. Mlle Guimard, a leading dancer at the Paris Opera, is even alleged to have staged pornographic performances at her private theatre in the 1770s. To this you can add any number of reputed (and occasionally substantiated) affairs between dancers and a multitude of crowned heads across Europe.

The late illustrious dance historian Ivor Guest, like many dance authors of his generation, peppers his histories of the Paris Opera with just these kinds of gossipy morsels about dancers’ off-stage lives, which he drew from his wide-ranging surveys of contemporary journals, newspapers and correspondence. These juicy insights are, in part, what make his histories so enjoyable and accessible to a non-specialist readership. But sources, be they texts or illustrations (and we must include even Degas’ paintings here) are inevitably constructed under the influence of certain interests, views or values. And that’s where the problems have arisen for dance historiography, which (and please pardon a gross generalisation here) has continued to be influenced by fairly literal interpretations of historical sources. What I observed, more precisely, was a relatively recent generation of dance authors and historians still wrestling with efforts to classify dancers according to morally-inflected understandings of professionalism, sexual status and celebrity.

At issue is not so much whether past generations of dancers actually sold sexual favours or faced sexual exploitation. As Felicity Nussbaum writes, “Unquestionably actresses peddled their talents, sexual and otherwise, in order to follow their passions and ambitions, or simply survive” – and what Nussbaum says of actresses is true of dancers too.2 In my article for Dance Research, however, I argue that dance scholarship has been slower to move away from the preoccupation with dancers’ sexual status. These days, scholars of British theatre offer up rich historical analyses of actresses and playhouse celebrities without getting bogged down trying to reconcile accounts of performers’ offstage ‘misdemeanours’ with favourable reports of domestic virtues and onstage achievements. By contrast, the ballerina’s “duality” as a “concubine or prostitute” and “artist of the highest order” continues to be put forward as a peculiarly important concept for our understandings of and approaches to ballet’s past.3

That’s a very long overture to introducing ‘Libertine Intrigues’, which surveys the issues outlined above, then hones in on the 18th-century ‘opera girl’ (used synonymously with ‘opera dancer’). The article uses the opera girl, a ubiquitous figure in 18th-century scandal and satire, to unpack some of the ways in which the period’s authors sensationalised opera girls’ sexuality and explains, more importantly, why they did so. From the texts that are considered, including fashionable periodicals, works of history, sentimental novels and prostitute narratives, it becomes clear that the opera girl fulfills a variety of rhetorical functions that distinguish her principally as a literary type; in other words, when 18th-century authors talk about opera girls, they are not especially interested in dancers’ real-life experiences. Get set for subtexts hinging on French suspicions of the French aristocracy, English suspicions of the French aristocracy, and English suspicions of the English aristocracy behaving like French aristocracy! The one real-life dancer we hear from is none too impressed by any of it.

‘Libertine Intrigues: Opera Girls in Eighteenth-Century British Discourse’ appears in the November 2019 issue of Dance Research. Access is available via the paywall of Edinburgh University Press (where you can also read the abstract), or free to those with database access via their institution.

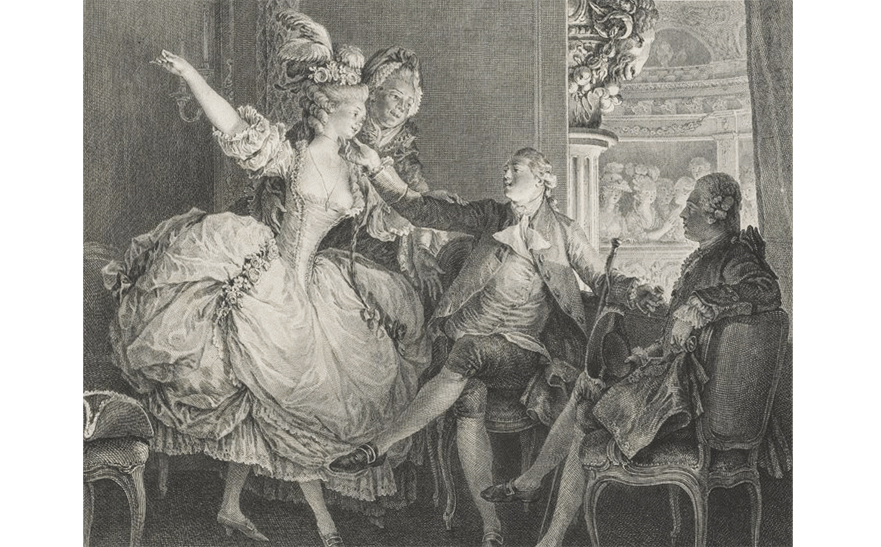

Illustration credit: La Petite Loge, after Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune, c. 1783. Bibliothèque nationale de France. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52507566t

‘Libertine Intrigues: Opera Girls in Eighteenth-Century British Discourse,’

Dance Research (Society of Dance Research, Edinburgh University Press)

vol. 37, no. 2 (2019): 239–256.

DOI: 10.3366/drs.2019.0275

Preparation of Libertine Intrigues was not supported by funding or waged employment.

- Jennifer Homans, Apollo’s Angels (New York: Random House, 2010), p. 64. ↩

- Felicity Nussbaum, Rival Queens: Actresses, Performance, and the Eighteenth-Century British Theater (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), p. 9. ↩

- Deirdre Kelly, Ballerina: Sex, Scandal and Suffering behind the Symbol of Perfection (Greystone Books, Vancouver, 2012), pp. 2–3. ↩

Leave a Reply